Alejandro Casona, a Boy in Besullo

The first five years of Alejandro Casona's life, which mark his life trajectory, took place in the "paradise" of Besullo. That's how the author himself remembered this stage decades later:

"Let me offer you two intimate confidences. I was a happy child in a town where three wonderful superlatives surrounded me:

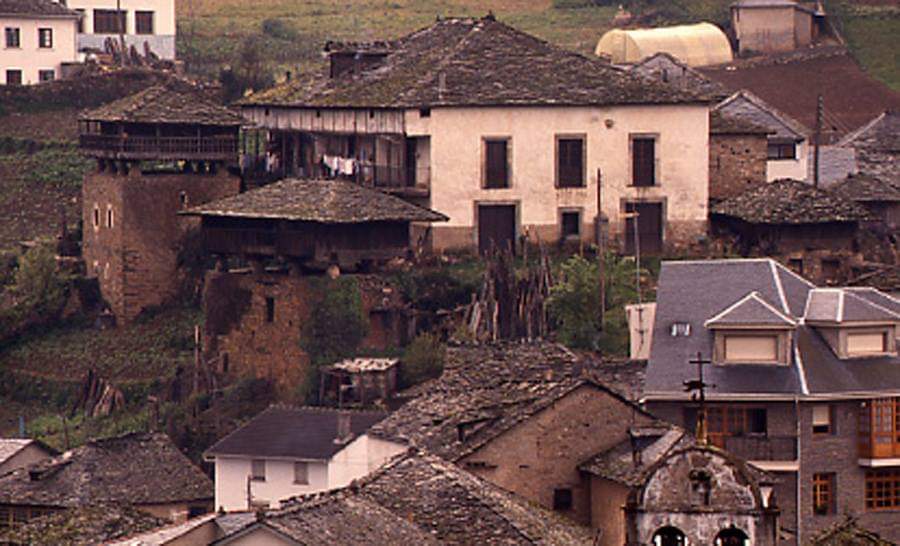

La Casona with its two paneras in Besullo (Cangas del Narcea)

La Casona, from which I took my literary name, where I went to school, and of which my parents were teachers.

El Corralón, with its gigantic wall.

El Portón, which was the central iron gate of the wall.

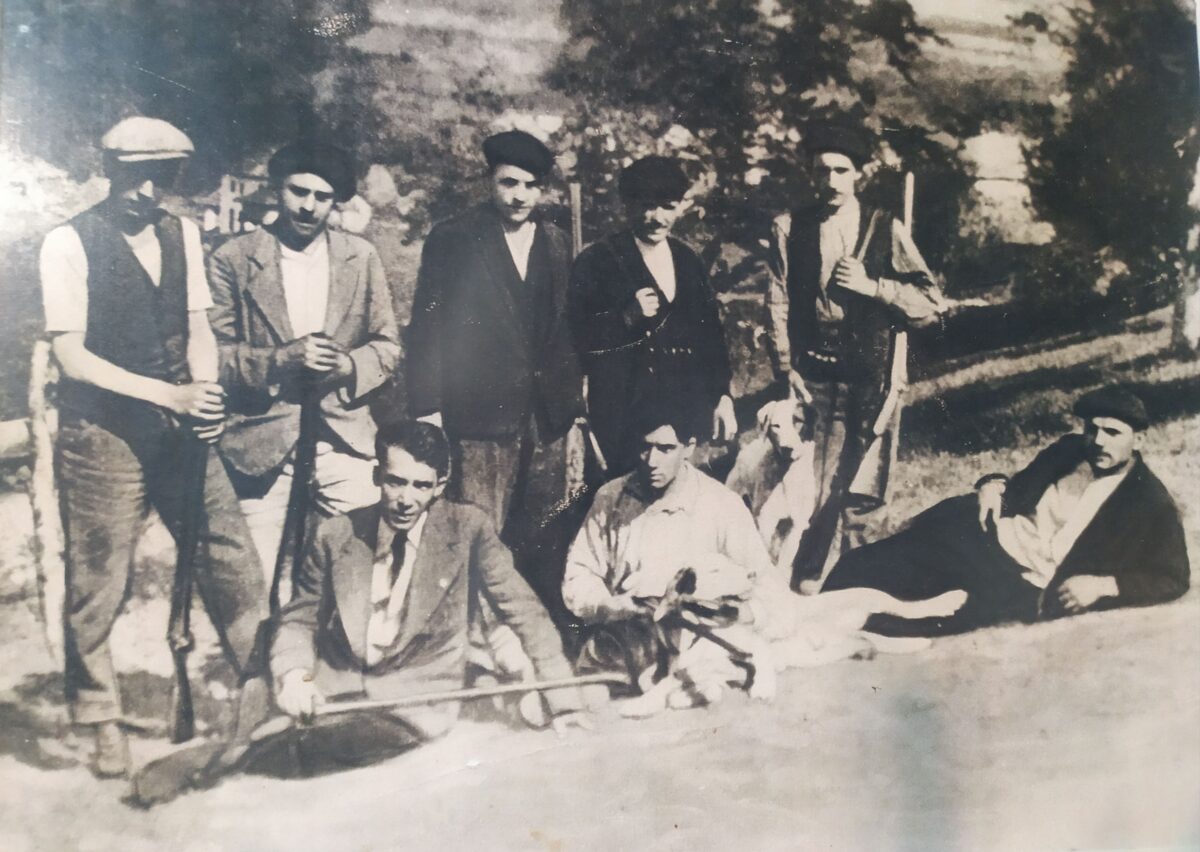

Casona (bottom left with shotgun), next to Besullo hunters

When I returned to Besullo as a man, La Casona was still a great manor house, far from that castle that reminded me of my childhood heart, La Muralla was a simple wall barely two meters high, and the Portón a simple nail door. Of course, my size was different, but my town had shrunk much more than I had grown.

I am from a poor family and village children do not have toys; but I had a sensational, fabulous toy in my childhood: a chestnut. It was a chestnut tree they called "La Castañalona". We know that when something is given a feminine and augmentative name here, it means "bigger." It was a chestnut tree ... I don't know! I cannot calculate its size. I remember it being tremendously large, with the trunk completely hollowed by lightning, without branches. Seven or eight of us children would fit inside it. There we played like Peter Pan, a bit like rabbits inside the tree. It was prodigious, because one day "La Castañalona" was a castle, another a ship, another a den of thieves, a palace, a forest ... A wonderful toy that was very difficult for a city child to have and we possessed without a doubt.

In my boyish village, we had a corral, smelling of cows and apples, of fluffy stable with ferns and heathers, in which one of my uncles, wounded in a distant war kept a beautiful saddle like an old chest. We also had an old chestnut tree that we could barely embrace among a few children, a blue-eyed donkey , and a secret entrance to an abandoned hermitage.

But among so many treasures, none fascinated me as much as that absent horse, that old saddle, in which I could gallop hours and hours of sleep. Rider in that chair, I was embarking on the most fabulous journeys, tense in the gold-keyed clogs; and there I began to discover in me, the first symptoms of an evil that I could never cure myself from: that I only liked to travel far, regardless of the time or the country, but far away.

Jovita Rodríguez, aunt and godmother of Casona, was a teacher in Besullo

In paved civilizations, when a child is attacked by this evil, he is cautiously entrusted to the care of a psychiatrist. Fortunately, my town, whose doctor pulled teeth and was paid in wheat, was too poor to feed psychiatrists; and my dear aunt, an herbal healer with a witch's chin and the hands of a virgin, loved to ride away, God knows on what magic broom of melancholy.

My village was so poor that we had nothing to show outsiders but a 100-year-old man, a single white horse, and a witch. She was a cheerful old woman, with her hooked nose sunk into her chin, and she healed with herbs and ancient words, and her great "aquelarre" on Saturday was half a bottle of frozen anise. Other countries with more cultured literature call this type of miraculous femininity a fairy, but here we know very well that a fairy is nothing more than a monarchical witch, who dresses in Paris "Chez Christian Lacroix". She was happy to scare us with a strange laugh when we met her on the mountain with her bundle of firewood on her back, but we boys adored her from afar, with that mixture of admiration and fear that is in all true worship. She also had the most beautiful apple tree in the city, of which only the first seven apples were reserved for her; all the others were for us, but on the condition that she that she did not give them to us, she let us steal them, perhaps thinking that we would enjoy them more that way. What I never knew was why she had to have exactly seven. They say it's a magic number!".